"We Sleep at Our Guns"

April 1-9, 1865

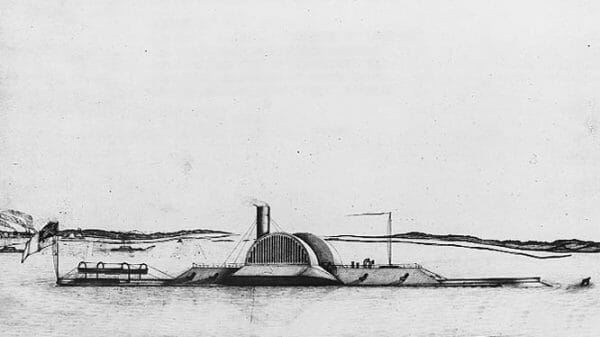

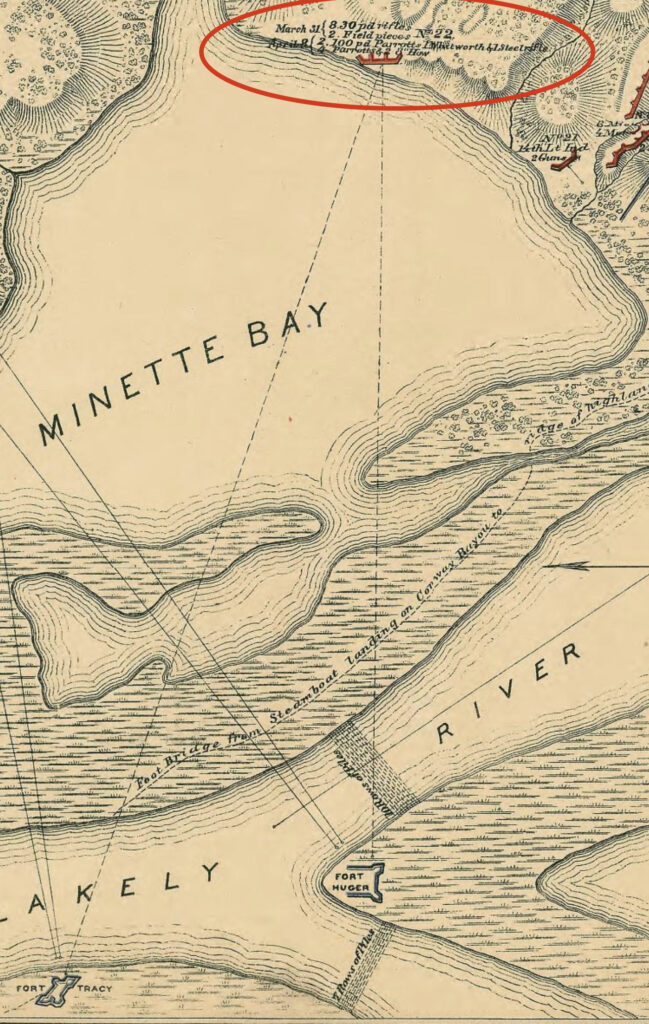

Although the new U.S. battery drove off the Nashville, Huger and Tracey only sustained minor damage. “One of the environs of Huger’s dining room was a pertinacious Indiana battery of Federal Parrott guns, ‘which faced our way too much,’ for between the mouthfuls of relished viands, there soared away from the Bay Minette,” recalled one Confederate. He had stopped off at Huger on his way from Mobile to Spanish Fort. “One of these Parrotts caged by Indianans was known to us by word of mouth, and its ears must have burned as we talked about it, for while we were still commenting, it let out a squawk and threw its projectile at a post nearby us, grazed the head of the sentry at the magazine, and cleared the quarters.” One soldier of the 22nd Consolidated Louisiana tried to comfort his girlfriend in a letter he sent from Huger: “Do not be uneasy as they have only small guns planted. They have thrown several hundred shells and shot at us, and yet nobody hurt.”[1]

Huger and Tracey held out in silence while enduring the Federal bombardment. “They annoy us, but so far, thank God, have done no damage,” remarked a private of the 22nd Louisiana Consolidated. “I am sitting at our big 10-inch gun where myself and the Sergt. sleep. It is about as safe a place as there is at the battery.” [2]

The garrisons at Huger and Tracey could hear constant firing at Spanish Fort, but they continued to ride out the siege in silence per their orders. “The Yankees fired about half dozen shots at us today. No damage done,” observed one Louisianan at Huger. “We sleep at our guns as the shanties here are exposed to the fire of the enemy.”[3]

On Monday, April 3, 1865, the Federal battery on the bluffs of Minette Bay fired their 30-pounder Parrotts and two Whitworth guns at Huger and Tracey during the bombardment. However, Major Washington Marks and his garrison remained quietly resolute. “The Yanks shelled us for a while quite furiously; nobody hurt. We are well protected,” a Louisiana artillerist wrote to his girlfriend. “So far, the Yanks have made a very poor fight as they have a host of men. I hope we will succeed in driving them back.”[4]

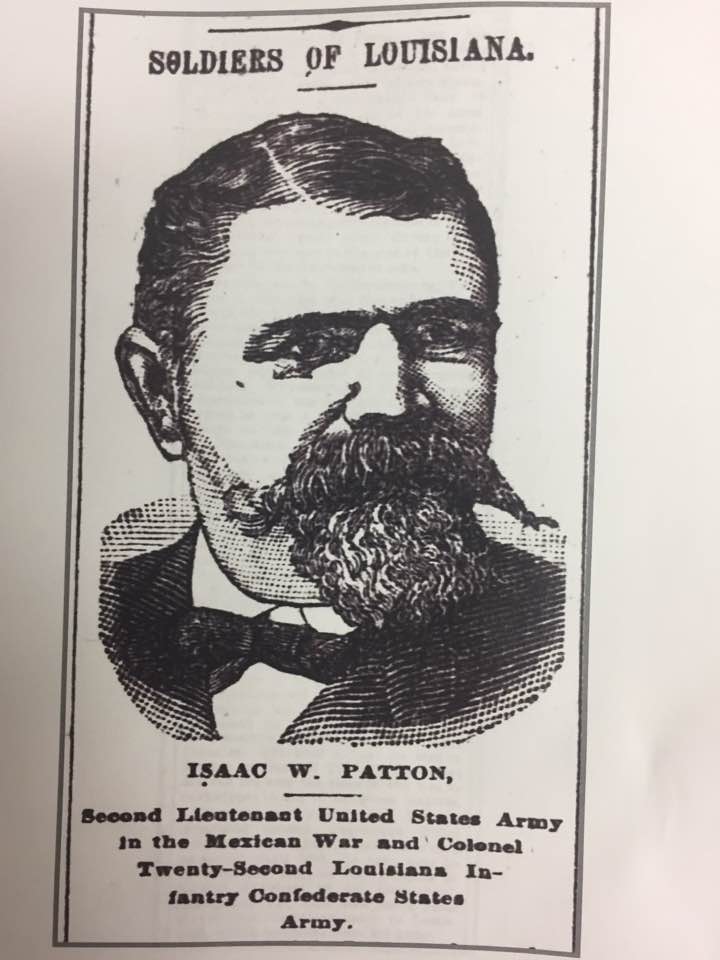

Near dusk on the evening of April 8, 1865, the Federals attacked and gained a lodgment at the fort’s northern flank. However, most of the Spanish Fort’s garrison escaped on a hidden treadway in the marsh that terminated opposite Battery Tracey, where boats collected them. As morning broke on April 9, 1865, the artillerists at Tracey observed the Federal columns crossing the Minette Creek pontoon bridge. Colonel Isaac W. Patton—who assumed direct command of Huger and Tracey after evacuating Spanish Fort—wired Liddell the grim news that heavy columns of blue-coated soldiers were marching his way. [5]

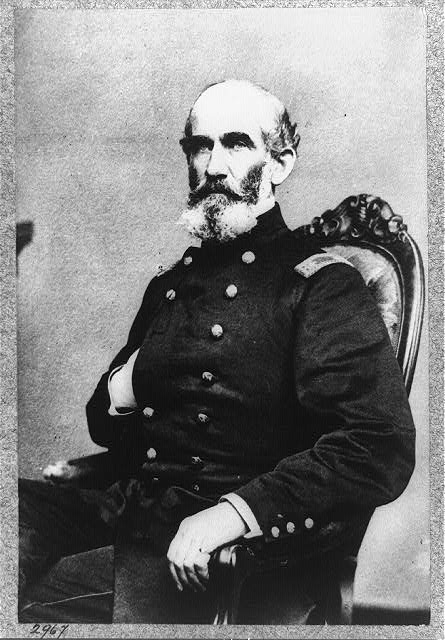

The possession of Spanish Fort gave the Federals command over the two forts. Immediately after the capture of Spanish Fort, the Minette Bay Battery sent eight shots at Huger with no reply. Spanish Fort’s Fort McDermott and old Spanish Fort also turned their guns on the Apalachee Batteries. Earlier, U.S. Major General A.J. Smith believed the forts were abandoned. However, the Southern artillerists would soon end their silence. The two forts would hold out three days after the capture of Spanish Fort. As U.S. General C.C. Andrews put it: “They were not days of quiet.” [6]

[1] Waterman 1900c, 22; Robert Tarleton and William Still, “The Civil War Letters of Robert Tarleton,” The Alabama Historical Quarterly 32, No. 1 (Spring 1970): 79; Letter, ML to AH, Apr 1, 1865.

[2] ORA 49, pt. 2, 1191-1192; “The Lady Slocomb,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, Sept 20, 1899,7; Letter, ML to AH, Apr 2, 1865; Maury, “Defence of Mobile in 1865,” 11; ORA 49, pt. 2, 1192.

[3] Letter, ML to AH, Apr 3, 1865.

[4] ORA 49, pt. 1, 95; Letter, ML to AH, Apr 4, 1865.

[5] ORA 49, pt. 2, 1219, 1222.

[6] Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile: 227; “Rebellion in the Gulf States Dead,” Chicago Tribune, Apr 18, 1865, 3; ORA 49, pt. 2, 182, 301; Arthur W. Bergeron, “The Twenty-Second Louisiana Consolidated Infantry in the Defense of Mobile,” The Alabama Historical Quarterly 38, no. 3 (Fall 1976): 212; Hewitt, Supplement to the Official Records, 946.