"These Were Not Days of Quiet"

April 9-12, 1865:

On April 9, the Federals assaulted and captured Fort Blakeley. At Battery Huger, the men found the news of the capture of Fort Blakeley disheartening. One soldier of the 22nd Louisiana observed: “Great many getting on logs and floating down the river were picked up by our boats. I have no doubts that as soon as the enemy makes their appearance in front of the city, it will be surrendered.” The Huger garrison could hear the alarm bells ringing from Mobile. They believed the Federals had already crossed over to the western side and marched on the city. The general impression prevailed at Huger that they would be cut off and taken prisoner.[1]

After Fort Blakeley fell, around 10 p.m., Maury called a council of war and decided to evacuate Mobile. With the evacuation decided, he issued the long-awaited orders to the eager artillerists at Huger and Tracey to open on the Federals at Spanish Fort. The Apalachee Batteries were the only obstacles left between Canby and the city. Federal artillery continually fired on them during the siege while the fleet to the south slowly continued their approach. Low on ammunition—they only had about 200 rounds of ammo for each cannon—the Apalachee Batteries had remained silent during the second week of the siege. Early the morning of April 10, however, Maury wired orders to Patton: “Open all your guns upon the enemy, keep up an active fire, and hold your position until you receive orders to retire.” Here, at last, was the awaited go-ahead the isolated artillerists wanted. “Fort Huger [and Tracy] now had some use for her heavy guns to turn upon Spanish Fort, occupied by the enemy,” remembered General Liddell. “The batteries were ordered to open fire, holding nothing back.” [2]

Despite their apprehension of being captured, they fired their guns to cover the evacuation of Mobile. Indeed, Patton’s artillerists unleashed their pent-up fury, “belching flame and smoke” on the besiegers at Spanish Fort. The continual cross-firing resembled a “grand crashing thunderstorm.” [3]

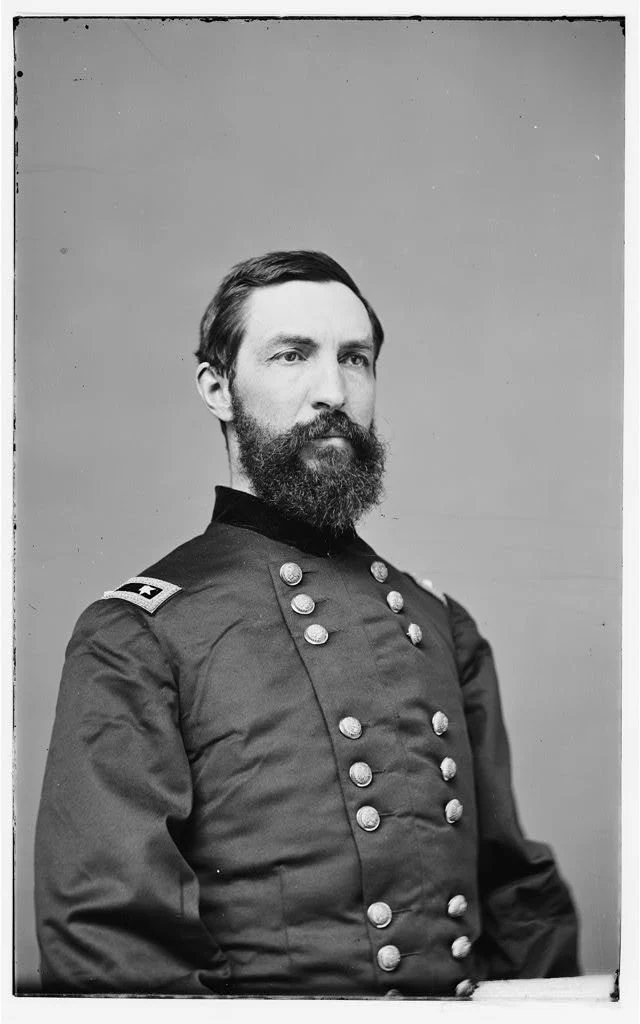

The two forts would hold out three days after the capture of Spanish Fort. As U.S. Brigadier General C.C. Andrews put it: “They were not days of quiet.”[4]

From April 9th through 11th, Patton’s artillerists at Huger found themselves exposed to the fire of several Federal batteries erected at Spanish Fort. The U.S. Navy posed another threat, as they had further cleared torpedoes on the Blakeley River, allowing the USS Octorara to steam up two thousand yards closer to their position. Everything remained quiet until noon when the gunboat open-fired from her new position, still nearly 3 miles from Battery Huger. The ominous puff came, followed by the shell. The men on the parapet joyously shouted that it “fell short,” followed by the exclamation, “Ah, old fellow, you cannot reach us here at all events.” These hopeful feelings were short-lived, for again came another shot in a direct line with the first, which plunged into the river three hundred beyond them. Then came another shell, this time hitting the center of their battery. From that moment on, every shot told on their bomb-proofs, and by their explosions, made the boggy foundations of Huger tremble like a ship in a gale of wind. [5]

“The artillery on the Bay kept up its sullen thunder till midnight and then went silent for a while till a fearful explosion shook the air,” Chaplain Elijah E. Edwards, 7th Minnesota, Marshall’s Brigade, noted, “from the blowing up of the magazines on the islands, and we knew that there was no longer an enemy before us.” Edwards’s claim that the Confederates blew up their magazines is questionable. Andrews did not mention an explosion at Huger or Tracey in his seminal book History of the Campaign of Mobile. [6]

In a letter to Andrews, written on June 17, 1866, Lieutenant Commander William W. Low, U.S. Navy, stated that around 9 p.m., a cutter of the Octorara on picket duty just south of Huger intercepted a skiff. There were eight men aboard, deserters from Huger, who informed the officer of the boat that Huger and Tracey had been evacuated just after dark. Contrary to Maury’s claim, the refugees told the naval officers that the armament and ordnance stores had not been destroyed. A landing was made, and the forts came into the possession of the Navy. Low did not indicate a magazine explosion had occurred, although he would have certainly seen one from his vantage point aboard the Octorara. That evening, pontoniers of the 114th Illinois learned of the evacuation. They went to the forts and inscribed on the cannons: “Eleven o’clock, P.M., April 11. Captured by the One Hundred and Fourteenth Illinois” and added their names. [7]

Most Federal artillery shots from Spanish Fort glanced harmlessly over the water. The ones that managed to hit the forts sent up clouds of dust, sand, or pieces of wood. “A shell sometimes exploded in the water and sent up a column of spray 100 feet in height,” Chaplain Elijah Edwards jotted in his journal. The batteries were frequently enveloped in smoke, while their shells often ricocheted along the water, creating “a line of spray like the sparks from a rocket though not so continuous.” Edwards observed what appeared to be a man standing on the parapets of Tracey throughout the galling fire. While the others on the parapets would vanish at the bursting of a shell, this heroic figure only disappeared in the smoke of the battle. “When it cleared, he was still there,” Edwards recalled, “like the flag ‘that so proudly we hailed at the twilight last gleaming.’ How I respected that stalwart but heroic rebel till a glass kindly lent by an officer revealed the fact that he was a wooden post. Still, he furnished our gunners with an excellent mark.” [8]

At Battery Huger, the men found the news of the capture of Fort Blakeley incredibly disheartening. One soldier of the 22nd Louisiana observed: “Great many getting on logs and floating down the river were picked up by our boats. I have no doubts that as soon as the enemy makes their appearance in front of the city, it will be surrendered.” The Huger garrison could hear the alarm bells ringing from Mobile. They believed the Federals had already crossed the western side and marched on the city. The general impression prevailed at Huger that they would be cut off and taken prisoner. [9]

Huger and Tracey relentlessly pounded the Federals for two days with their heavy fire. With the restraint of conserving their ammunition lifted, they showed a defiant front to the U.S.-occupied Spanish Fort, the Bay Minette Batteries, and the double-ender Octorara. “So long as the obstructions at Huger held good—the ten rows of piles across Apalachee River and seven rows crossing Blakely—the Blakely River was barred to Uncle Samuel’s navy,” recalled Acting Master Mate George S. Waterman, C.S.N. “It was their last chance at the big guns, though they didn’t know it, not only in the siege of Mobile but the last grand bombardment of the civil war.” [10]

On Tuesday, April 11, 1865, Canby ordered the Indiana battery on Minette Bay to fire another 100-gun salute at Huger and Tracey. The salute commenced at 8 a.m. with great rapidity. However, Patton’s men responded with continuous and vigorous concentrated fire from Huger and Tracey’s heavy rifled guns. “Their shells were constantly striking my works or exploding over and around us,” reported an officer of the 1st Indiana Heavy Artillery. “Everyone who witnessed this engagement of the 11th claim that on no other occasion has the fire from the enemy’s artillery been so heavy and constant during the whole siege.” The officer claimed they received nearly 400 shots during the day from the two heavily mounted earthworks on the Apalachee River. [11]

The Apalachee Batteries continually bombarded Spanish Fort throughout the day. “This forenoon, we moved about 2 miles to get out of the range of the rebel shells when our battery opened on them,” a soldier of the 95th Illinois recorded in his diary. [12]

“About 10 a.m. of the 11th, we had to ‘dig out’ of our camp as one of the rebel batteries had got our range and, with their usual ‘cussedness,’ were dropping seven-inch shells in among us in a manner that was not very favorable to longevity or good digestion,” noted a hospital steward of Hubbard’s Brigade of McArthur’s Division. “So out of respect for their openly expressed aversion to keeping good company, we “packed up our kit” and moved up the river a mile or so out of range.” [13]

Meanwhile, at Batteries Huger and Tracey, Patton’s men continued firing with great vigor, trying to use up all their ammunition. “Two hundred fifty shells were hurled April 9-11 at forts and fleet by Huger and Tracey. Wasn’t that “great guns” work?” recollected Waterman. The Federals at Spanish Fort responded in kind with cannon fire that killed Huger artillerists Corp. Isidore Dinguidard and wounded Priv. A. L. Duvigneaud during the day. [14]

The cannon fire continued “heavy and grand” throughout the day. Andrews noted the historical significance of the artillery bombardment: “It was the last day for great guns in Mobile Bay—the last for the war. The smoke rolled up in cloudy columns.”[15] In Mobile, citizens could hear the heavy artillery. “As the guns upon forts Huger & Tracy boom out with a heavy roar, the sound fills my heart with bitter sorrow,” Mobile resident Laura Pillans noted in her diary. [16]

Late that night, Maury sent one of his staff officers to Tracey to inform Patton they could retire. The garrisons of Huger and Tracey spiked their cannons and evacuated. Patton withdrew his men on a treadway bridge from the rear of Tracey. The pier reached out nearly two miles to Conway Bayou, beyond the range of the Federal guns. The first steamer Maury sent to them grounded, and at about 2 a.m., he dispatched another. Maury pointed out that the men were brought safely off with their small arms and ammunition. They dismantled their batteries before they abandoned them Wednesday morning after daylight before leaving Mobile’s wharf for Demopolis. [17]

“The artillery on the Bay kept up its sullen thunder till midnight and then went silent for a while till a fearful explosion shook the air,” Chaplain Edwards noted, “from the blowing up of the magazines on the islands, and we knew that there was no longer an enemy before us.” Edwards’s claim that the Confederates blew up their magazines is questionable. General C.C. Andrews did not mention an explosion at Huger or Tracey in his seminal book History of the Campaign of Mobile.[18]

In a letter to Andrews on June 17, 1866, Lt. Commander William W. Low, U.S. Navy, stated that around 9 p.m., a cutter of the Octorara on picket duty just south of Huger intercepted a skiff. There were eight men aboard, deserters from Huger, who informed the officer of the boat that Huger and Tracey had been evacuated just after dark. Contrary to Maury’s claim, the refugees told the naval officers that the armament and ordnance stores had not been destroyed. A landing was made, and the forts came into the possession of the U.S. Navy. Low did not indicate a magazine explosion had occurred, although he would have certainly seen one from his vantage point aboard the Octorara. That evening, pontoniers of the 114th Illinois learned of the evacuation. They went to the forts and inscribed on the cannons: “Eleven o’clock, P.M., April 11. Captured by the One Hundred and Fourteenth Illinois” and added their names. [19]

Ann Quigley, Head Mistress of the Mobile public school, Barton Academy, observed in her diary: “Tis over. The last gun has been fired—the last soldier has marched out [of Mobile].” [20]

In Hindsight:

Before the siege, General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Department of the West, considered it a mistake to garrison any part of Baldwin County, Spanish Fort, and Fort Blakeley. He believed that Huger and Tracey should have been made self-sustaining forts and that the main garrison should have remained in Mobile. In hindsight, Maury conceded too that it was an error to fortify or occupy the positions of Spanish Fort and Fort Blakeley. “No batteries from these bluffs could seriously harm batteries Huger and Tracey,” Maury purported. The battery near Bayou Minette bridge was in as good a position as could have been selected upon that site; about 2,700 yards from battery Huger, it bombarded both forts for several days without causing severe damage.

With time, however, the U.S. batteries established late in the siege, north of Spanish Fort, on the shore of Minette Bay, would have made holding Huger and Tracey untenable. If the question of defending the Blakeley River were again presented, Maury would have made Huger and Tracey stronger, self-sustaining works as Beauregard had initially suggested. “If the Eastern Shore were to be occupied at all, a strong work on the Redoubt McDermott would accomplish the object sought,” he concluded. The Rebels expended a tremendous amount of artillery ammunition while defending the two forts. The capture of the Selma arsenal, where their ammunition was manufactured, further exacerbated the issue. After the capture of Fort Blakeley, not enough ammunition remained to justify an attempt to defend Mobile.[21]

- [1] Andrews, Letter, ML to AH, Apr 10, 1865; Christopher C. Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile: Including the Cooperative Operations of Gen. Wilson’s Cavalry in Alabama (New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1889), 227.

- [2] Liddell, Liddell’s Record, 195.

- [3] Maury, “Defence of Mobile,” 9-10; Edwards Journal, Apr 13, 1865, 256-257.

- [4] Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile: 227.

- [5] Army and Navy Journal, Dec 16, 1865; Newspaper clipping, C.C. Andrews Papers, 1866,

- MNHS, St. Paul, MN; Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 227-229.

- [6] Maury, “Defence of Mobile,” 10; Elijah E. Edwards, Journal, Mar 25, 1865, Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS), St. Paul, MN, 260. Typescript, hereafter Edwards Journal, Mar 25, 1865; Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 231.

- [7] Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 231; Letter, W.W. Low to C.C. Andrews, June 17, 1866, C.C. Andrews Papers, MNHS.

- [8] Edwards Journal, Apr 13, 1865, 256-257.

- [9] Letter, ML to AH, Apr 10, 1865.

- [10] Miller, Captain Edward Gee Miller, 31; Waterman 1900b, 55. The Blakeley River had ten rows of piles and the Apalachee had seven rows of piles.

- [11] Letter, Samuel Armstrong to Benjamin Hays, Apr 10, 1865, C.C. Andrews Papers, MNHS.

- [12] Ridge Diary, Apr 11, 1865.

- [13] John M. Williams, The “Eagle Regiment,”: 8th Wis. Inf’ty. Vols. A Sketch of Its Marches, Battles and Campaigns. From 1861 to 1865. With a Complete Regimental and Company Roster, and a Few Portraits and Sketches of Its Officers and Commanders (Belleville, WI: Recorder Print, 1890), 97.

- [14] Bergeron, “The Twenty-Second Louisiana Consolidated Infantry in the Defense of Mobile,” 212; Maury, “The Defense of Mobile in 1865,” 9, 10; Waterman 1900b, 55.

- [15] Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 230.

- [16] Laura Roberts Pillans, “Diary of Mrs. Laura Roberts Pillans, 11 July 1863 – 2 November 1865,” History Museum of Mobile, Mobile, AL

- [17] Maury, “Defence of Spanish Fort,” 131; Maury, “Defence of Mobile,” 10; Waterman 1900b, 55; Bergeron, “The Twenty-Second Louisiana Consolidated Infantry in the Defense of Mobile,” 212. Maury incorrectly wrote Chocaloochee Bayou, but it was Conway Bayou.

- [18] Maury, “Defence of Mobile,” 10; Edwards Journal, Apr 13, 1865, 260; Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 231.

- [19] Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 231; Letter, W.W. Low to C.C. Andrews, June 17, 1866, C.C. Andrews Papers, MNHS.

- [20] Ann Quigley, “The Diary of Ann Quigley,” Gulf Coast Historical Review 4, no. 2 (Spring 1989): 89–98.

- [21] Maury, “Souvenirs of the War”; Andrews, History of the Campaign of Mobile, 70-71.